How long can we continue to exceed planetary limits?

By Natacha Gondran, Mines Saint-Étienne, UMR 5600 Environment, City, Society (EVS), and Aurélien Boutaud, associate researcher at UMR 5600 EVS.

In recent months, several scientific papers months have drawn attention to the fact that new planetary limits have been crossed (e.g., here and here). These worrying observations have been the subject of numerous media reports.

But what do scientists mean by planetary limits? How should we interpret these facts? Finally, should we really be worried?

The Earth system has been operating under the Holocene for the last 11,000 years

To answer these questions, we must turn to the researchers studying these planetary limits, who work in a disciplinary field called Earth System Science.

They consider the planet as an entity that involves complex interactions between the atmosphere, the lithosphere and the biosphere (living elements). Like any system, the Earth is endowed with adaptive capacities that allow it to maintain a state of dynamic equilibrium between these elements – this state of relative stability is sometimes referred to as a “regime”.

However, this balance is sometimes upset, to the point that the Earth system starts to work very differently.

For example, the Quaternary Period (which began about 2.6 million years ago) has been marked by regular climate changes. Because of variations in the Earth’s position in relation to the Sun, the climate of our planet has shifted regularly between ice ages (which lasted up to 100,000 years) and interglacial periods (which were generally shorter).

For over 10,000 years, we have been living in a period of the Earth’s system that geologists call the Holocene.

The Holocene has proven to be particularly favorable to human development. The good news is that this epoch is expected to last for over 10,000 years. The bad news is that we are threatening the balance of this system. In other words, we are teetering on the edge.

Exceeding a planetary limit means crossing a tipping point that will take us out of the Holocene

The scientific literature on planetary limits is largely based on the concept of a tipping point, but what does this mean exactly?

In a period such as the Holocene, the terrestrial ecosystem is endowed with regulatory capacities that allow it to absorb disturbances, called “negative feedbacks”. For example, if there is an abnormal increase in CO2 emissions, part of this CO2 will be sequestered by the oceans to limit the climatic perturbations.

Unfortunately, these shock absorbers sometimes snap, like a rubber band pulled too tight. This is when “positive feedbacks” come into action.

For example, as it warms, the permafrost releases large quantities of methane into the atmosphere, which increase the greenhouse effect and thus global warming.

As it warms, permafrost becomes unstable and cracks. Dentren/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Once set in motion, these phenomena amplify and accelerate the perturbance, to the point of making any return to normality impossible. A change of epoch then becomes inevitable: the climate will find a new state of equilibrium, characterized by the greenhouse effect and temperatures much higher than those of the Holocene.

Some scientists talk of a “Hothouse Earth” scenario, which would have cataclysmic effects on all the variables of the Earth system.

Important: crossing a planetary boundary is not the same as exceeding a limit!

However, scientists are faced with a major problem: it is extremely difficult to precisely determine when a tipping point might be reached.

Aware of the dangers of exceeding such limits, scientists are urging decision makers to avoid crossing the lower bounds of uncertainty. They propose to call this lower limit a “planetary boundary”.

To better understand the difference between a limit and boundary, let us imagine the case of a frozen lake, where the ice becomes thinner further away from the shore. Even if we know the thickness of the ice in several places, it is very difficult to determine at what point the ice will break under a person’s weight. At best, we could say beyond five meters, for example, a risk develops. This is the value that constitutes a “boundary”.

In terms of the climate, models show that below a concentration of 350 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere, the Holocene Epoch is not threatened. If we exceed 500 ppm, on the other hand, a climate system shift is almost guaranteed. The planetary limit is located somewhere between these two values.

However, we have already crossed the threshold of 420 ppm, and have therefore exceeded the planetary boundary.

But have we crossed the tipping point? The answer remains unknown. The only thing we know for sure is that we are playing with fire, a bit like someone who has decided to venture further out onto a frozen lake, beyond the previously mentioned safety zone…

In addition to the climate, several planetary boundaries have already been crossed

The situation is all the more worrying given that the climate is not the only element of the Earth system that has been seriously affected.

Biodiversity, which conditions the resilience of the biosphere, is dangerously threatened. The biogeochemical cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus have been profoundly affected by intensive farming, to the point of creating vast “dead zones” in the oceans. Deforestation has generated imbalances in the water and climate cycles that have now reached a global scale.

More recently, attention has been drawn to the impact of chemical pollutants and the worrying decrease of water content in soils.

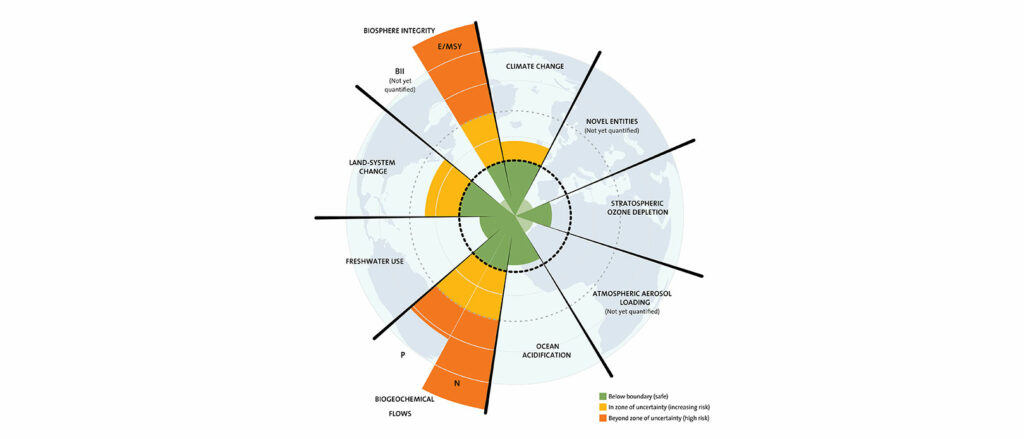

Of the nine planetary boundaries monitored today, at least five have been crossed – and even six, if we take into account the most recently published study.

Out of the 9 Earth system boundaries, at least 5 have now been crossed. Stockholm Resilience Centre, CC BY

This does not mean that the worst is sure to happen, but the increasing warning signs should certainly call our attention: we are on the verge of provoking a shift out of the Holocene, the consequences of which would be catastrophic.

The transition must not only be climatic, but also ecosystemic

What must human societies learn from this?

Firstly, we must understand that the climate is central to maintaining the planetary equilibrium and that anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases must be stopped urgently.

Secondly, it is important to integrate the pluralistic dimension of the problem. Despite its importance, climate change must not be resolved at the expense of other global variables. For example, measures to massively increase the use of biomass or darken the atmosphere to limit solar radiation could have disastrous effects on other fundamental variables of the Earth system.

Finally, we must favor solutions that tackle the root of the problem and cease to imagine that we will be able to avoid exceeding planetary limits using technology alone.

Remaining within these limits also requires economic, social, cultural, political and geopolitical innovations. In other words, it is undoubtedly a question of exceeding a different limit: that of our imagination.

Aurélien Boutaud, Doctor in Environmental Science and Engineering, Mines Saint-Étienne – Institut Mines-Télécom and Natacha Gondran, Faculty Member in Environmental Evaluation, Mines Saint-Étienne – Institut Mines-Télécom

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (in French).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!