Four flagship measurements of the GDPR for the economy

Patrick Waelbroeck, Professor in Economic Sciences, Télécom ParisTech, Institut Mines-Télécom (IMT)

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

[dropcap]N[/dropcap]umerous scandals concerning data theft or misuse that have shaken the media in recent years have highlighted the importance of data protection. The implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe is designed to do just that through four flagship measurements: seals of trust, accountability, data portability and pseudonymization. We explain how.

Data: potential negative externalities

The misuse of data can lead to identity theft, cyberbullying, disclosure of private information, fraudulent use of bank details or, less serious but nevertheless condemnable, price discrimination or the display of unwanted ads whether they are targeted or not.

All these practices can be assimilated to “negative externalities”. In economics, a negative externality results from a failing in the market. It occurs when the actions of an economic actor have a negative effect on other actors with no offset linked to a market mechanism.

In the case of the misuse of data, negative externalities are caused for the consumer by companies that collect too much data in relation to the social optimum. In terms of economics, their existence justifies the protection of personal data.

The black box society

The user is not always aware of the consequences of data processing carried out by companies working in digital technology, and the collection of personal data can generate risks if an internet user leaves unintentional records in their browser history.

Indeed, digital technology completely changes the conditions of exchange because of the information asymmetry that it engenders, in what Frank Pasquale, a legal expert at the University of Maryland, calls the “black box society”: users of digital tools are unaware of both the use of their personal data and the volume of data exchanged by the companies collecting it. There are three reasons for this.

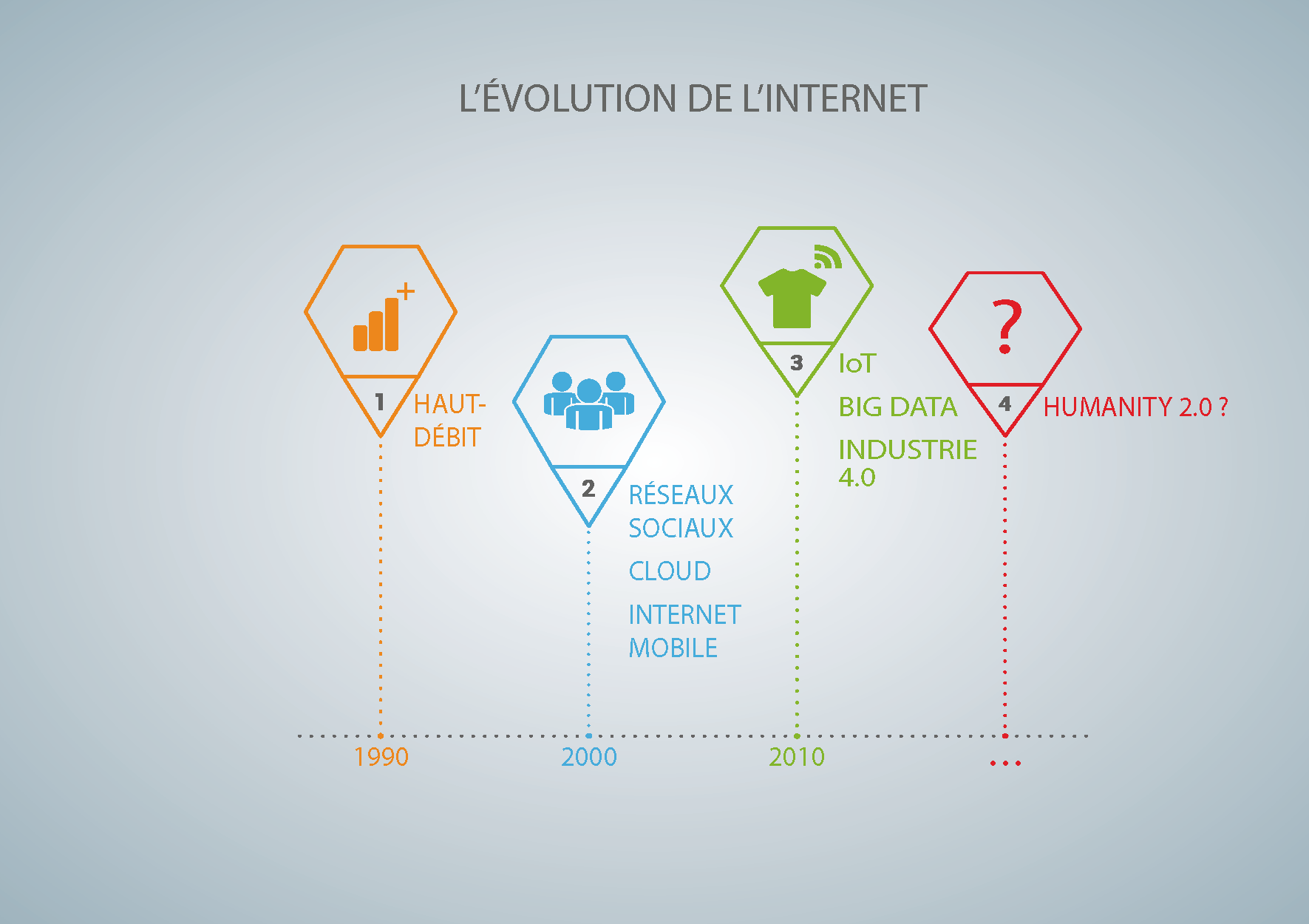

Firstly, it is difficult for a consumer to check how their data is used by the companies collecting and processing it, and it is even more difficult to know whether this use is compliant with legislation or not. This is even more true in the age of “Big Data”, where separate databases containing little personal information can be easily combined to identify a person. Secondly, an individual struggles to technically assess the level of computer security protecting their data during transmission and storage. Thirdly, information asymmetries undermine the equity and reciprocity in the transaction and create a feeling of powerlessness among internet users, who find themselves alone facing the digital giants (what sociologists call informational capitalism).

Seals and marks of trust

The economic stakes are high. In his work that earned him the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, George Akerlof showed that situations of information asymmetry could lead to the disappearance of markets. The digital economy is not immune to this theory, and the deterioration of trust creates risks that may lead some users to “disconnect”.

In this context, the GDPR strongly encourages (but does not require) seals and marks of trust that allow Internet users to better comprehend the dangers of the transaction. Highly common in the agri-food industry, these seals are marks such as logos, color codes and letters that prove compliance with regulations in force. Can we count on these seals to have a positive economic impact for the digital economy?

What impacts do seals have?

Generally speaking, there are three positive economic effects of seals: a signaling effect, price effect and an effect on quantity.

In economics, seals and other marks of confidence are apprehended by signaling theory. This theory aims to solve the problems of information asymmetry by sending a costly signal that the consumer can interpret as proof of good practice. The costlier the signal, the greater its impact.

Economic studies on seals show that they generally have a positive impact on prices, which in turn boosts reputation and quantities sold. In the case of seals and marks of trust for personal data protection, we can expect a greater effect on volume than on prices, in particular for non-retail websites or those offering free services.

However, existing studies on seals also show that the economic impacts are all the more substantial when the perceived risks are greater. In the case of agri-food certifications, health risks can be a major concern; but risks related to data theft are still little known about among the general public. From this point of view, seals may have a mixed effect.

Other questions also remain unanswered: should seal certification be carried out by public or private organizations? How should the process of certification be financed? How will the different seals coexist? Is there not a risk of confusion for internet users? If the seal is too expensive, is there not a danger that small businesses won’t be able to become certified?

In reality, less than 15% of websites among the top 50 for online audience rates currently display a data protection seal. Will GDPR change this situation?

Accountability and fines

The revelations of the Snowden affair on the large-scale surveillance by States have also created a sense of distrust towards operators of the digital economy. To the extent that, in 2015, 21% of Internet users were prepared not to share any information at all, whereas this was true of only 5% in 2009. Is there a societal cost to the “everything for free” era on the Internet?

Instances of customer data theft among companies such as Yahoo, Equifax, eBay, Sony, LinkedIn or, more recently, Cambridge Analytica and Exactis, number in the millions. These incidents are too rarely followed up by sanctions. The GDPR establishes a principle of accountability which forces companies to be able to demonstrate that their data processing is compliant with the requirements laid down by the GDPR. The regulation also introduces a large fine that can be as much as 4% of worldwide consolidated turnover in the event of failure to comply.

These measures are a step in the right direction because people trust an economic system if they know that unacceptable behavior will be punished.

Data portability

The GDPR establishes another principle with an economic aim: data portability. Like the mobile telephony sector where number portability has helped boost competition, the regulation aims to generate similar beneficial effects for internet users. However, there is a major difference between the mobile telephony industry and the internet economy.

Economies of scale in data storage and use and the existence of network externalities on multi-sided online platforms (platforms that serve as an intermediary between several groups of economic players) have created internet monopolies. In 2017, for example, Google processed more than 88% of online searches in the world.

In addition, the online storage of information benefits users of digital services by allowing them to connect automatically and save their preferences and browser history. This creates a “data lock-in” situation resulting from the captivity of loyal users of the service and characterized by high costs of changing. Where can you go if you leave Facebook? This situation allows monopolizing companies to impose conditions of use of their services, facilitating large-scale exploitation of customer data, sometimes at the users’ expense. Consequently, the relationship between data portability and competition is like a “Catch-22”: portability is supposed to create competition, but portability is not possible without competition.

Pseudonymization and explicit consent

The question of trust in data use also concerns the economic value of anonymity. In a simplistic theory, we can suppose that there is an arbitration between economic value on the one hand and the protection of privacy and anonymity on the other. In this theory there are two extreme situations: one in which a person is fully identified and likely to receive targeted offers, and another in which the person is anonymous. In the first case, there is maximum economic value, while in the second the data is of no value.

If we move along the scale towards the targeting end, economic value is increased to the detriment of the protection of privacy. Conversely, if we protect privacy, the economic value of the data is reduced. This theory does not account for the challenges raised by trust in data use. To develop a long-term client relationship, it is important to think in terms of risks and externalities for the customer. There is therefore an economic value to the protection of privacy, which revolves around long-term relationships, the notion of trust, the guarantee of freedom of choice, independence and the absence of discrimination.

The principles of pseudonymization and explicit consent in the GDPR adopt this approach. Nevertheless, the main actors have to play along and comply, something which still seems far from being the case: barely a month after the date of effect of the regulations, the Consumer Council of Norway (Forbrukerrådet), an independent organization funded by the Norwegian Government, accused Facebook and Google of manipulating internet users to encourage them to share their personal information.

Patrick Waelbroeck, Professor in Economic Sciences, Télécom ParisTech, Institut Mines-Télécom (IMT)

The original version of this article (in French) was published on The Conversation.

Also read on I’MTech :

[one_half]

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

[/one_half_last]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!