Simulation and serious games: training tools for crisis management

To prepare elected officials, local authorities and citizens to respond in times of crises, immersive simulations and serious games are particularly useful. At IMT Mines Alès and Mines Saint-Étienne, these techniques are used to help prepare people for the worst.

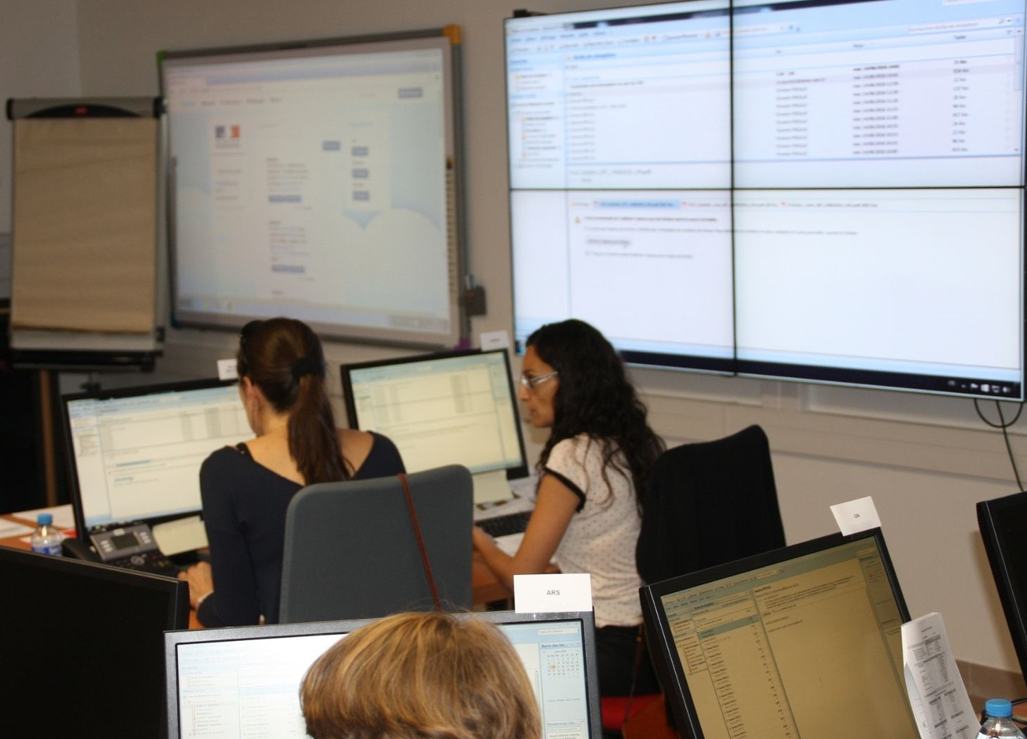

Several sirens are blaring in a chilly room at IMT Mines Alès. Staff from the local water utility met in an emergency this morning to form a crisis unit. An industrial incident has polluted the river that supplies the town’s drinking water. The unit’s decision-makers are inundated with calls from journalists and associations. At the same time, tweets by the local media are flooding onto the unit’s computer screens while news clips play out on the wall of screens in the room. The members are planning actions but communication between them is not always easy. Tensions starts to rise. Three hours after first addressing the incident, the crisis unit is dissolved. The participants leave the room. It is time for the debriefing, the simulation is over.

“Sensory immersion is an effective way to carry out crisis management exercises,” says Florian Tena-Chollet, a researcher in Crisis Simulation at IMT Mines Alès. The simulation described above took place at Simulcrise, a platform for simulating crisis management in situations that are as realistic as possible. It is “a research, teaching and training platform for students and researchers at IMT and different universities, such as those in Montpellier, Avignon and Nîmes,” the researcher explains. The platform is also available for use by professionals. Last June, participants from the French Centre for Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution took part in a simulation on water pollution.

A typical simulation begins by “setting up the context, which usually starts a few hours or days beforehand,” says Florian Tena-Chollet. “Before they arrive on site, participants start to receive weather reports with the day and time. The simulation day itself begins with a briefing during which we remind the participants of their role, the organization they represent and whether it is their own or another organization,” the researcher explains. On the day of the simulation, the simulation assistants send out the information that marks the start of the crisis. For a case of water pollution, it could be a message from a local council, which has received calls from residents who have noticed several dead fish in the town’s river. This is the signal for the participants to form the crisis unit in the simulation room.

Technology for an immersive experience in a real environment

The Simulcrise platform is composed of four rooms.* “Two rooms are dedicated to the trainees, while a central room is dedicated to the assistants participating in the exercise who set off the stimuli and play the roles of stakeholders in the outside world,” explains Philippe Bouillet, a computer engineer at IMT Mines Alès. Lastly, there is a technical control room where the computers, screens and speakers are managed.

Loudspeakers installed across the ceiling emit sounds from the local environment, such as rainfall in a flood scenario or sirens to mimic the coming and going of fire services and ambulances. The rooms are even equipped with reversible air conditioning, allowing the temperature to be adjusted according to the scenario. For example, if the scenario is based in La Réunion, the temperature can be adjusted to recreate the island’s weather conditions.

IMT Mines Alès has also developed a simulation of the Twitter interface, called Twitter-Like. The advantage of this is that the tweets published by the simulation assistants circulate on the Simulcrisis network and not on the internet. “We sometimes call in professionals, such as journalists, who play themselves in the simulation,” says Philippe Bouillet. To make the situation as realistic for the participants as possible, one of the research objectives is “to transpose the Simulcrisis tools and methods into organizations’ real crisis units,” says Florian Tena-Chollet. “For new scenarios, we use a multi-agent system based on artificial intelligence technology to make our simulations even more realistic,” says the scientist.

In addition, during the simulation, the researchers “watch for misunderstandings, misjudgments and the emergence of conflict, and note whether the team regularly gathers to review the situation,” explains Florian Tena-Chollet. Hidden behind tinted glass in an adjacent room or stationed in the room with the participants, the researchers observe interpersonal interactions and how information flows within the team. Once the simulation is over, the researchers hold a debriefing with the participants, during which they highlight existing good practices and identify areas for improvement in the way crises are managed.

Crisis management and board games

At Mines Saint-Étienne, another simulation tool has been developed, called Cit’In-Crise,** which is an educational game for teaching the general public, schoolchildren aged 9-12 and elected officials about crisis management in the event of flooding. “For elected officials, the game is an operational tool to help understand the municipal safety plan, which defines the process that the town or city will implement to deal with major industrial incidents or natural disasters,” says Eric Piatyszek, a researcher on territorial resilience at Mines Saint-Étienne.

A game of Cit’in Crise lasts about two hours and requires between 7 and 13 players. For the first 45 minutes, two assistants “describe the municipality in which the crisis to be managed is taking place, present the timeline of events and explain the role of each player,” says Eric Piatyszek. The assistants also explain the rules of the game and how to use the accessories.

The players are divided into two teams which are each assigned to a room. One team forms the crisis unit while the other forms the “story” team. The players in the crisis unit play the role of people such as the mayor and “the main officials who have to make decisions to save and protect the town,” says Eric Piatyszek. The players on the other team play characters outside the crisis unit, such as the local prefect or residents. Each team is joined by an assistant who monitors the progress of the game.

The game includes boards, cards and tokens to make the simulation fun. Special equipment is sometimes used to create radio news alerts, weather reports, or fire service and police sirens. Simulcrise’s imitation Twitter tool is also used. The game includes walkie-talkies and telephones so that the two teams can communicate with each other from their separate rooms. A digital interactive map allows the players to track the actions taken to manage the crisis.

A mobile and adaptable game

Since 2020, Cit’In Crise sessions have been held more than one hundred times, including a dozen events for one hundred or so elected officials. One of the reasons for the game’s success is the adaptability of the scenarios. “To start with, the game was only designed for the Rhône region, but we have since extended it to Gironde,” says Eric Piatyszek. “Flood issues are not the same: the Rhône river is subject to slow-rising fluvial floods while the Gironde is affected by fluvio-maritime surges that can cause flooding depending on factors such as the wind,” he continues. The scenario could be adapted to other geographical areas according to requests.

Making things fun is one of the most important aspects of Cit’in Crise and Simulcrise. Role-playing games in which players are subjected to sensory stimuli are recognized as being a good way to learn. For Eric Piatyszek, the game he designed seems effective. He now plans to conduct a survey of elected officials who have played Cit’in Crise to find out “whether the game has allowed them to implement new crisis management initiatives and whether it has changed their perception of crisis management,” he says. This is one of the key concerns of this research: it must above all help crisis management actors and citizens to better cope with disasters, whether natural or not.

Rémy Fauvel

* The four Simulcrise rooms are located in the Robert Casso Institute of Risk Sciences (ISR) building, co-financed by Europe (FEDER), the Languedoc-Roussillon Region and the Alès Area Industrialization Fund.

** Cit’In Crise was co-developed between 2017 and 2020 by the CNRS UMR 5600 EVS of Mines Saint-Étienne, IMT Mines Alès, La Rotonde and Les petits débrouillards. The project was supported by the Occitanie region, the European ERDF fund and the Vaucluse department.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!