Marine oil pollution detected from space

Whether it is due to oil spills or cleaning out of tanks at sea, radar satellites can detect any oil slick on the ocean’s surface. Over 15 years ago, René Garello and his team from IMT Atlantique worked on the first proof of concept for this idea to monitor oil pollution from space. Today, they are continuing to work on this technology, which they now use in partnership with maritime law enforcement. René Garello explains to us how this technology works, and what is being done to continue improving it.

Most people think of oil pollution as oils spills, but is this the most serious form of marine oil pollution?

René Garello: The accidents which cause oil spills are spectacular, but rare. If we look at the amount of oil dumped into the seas and oceans, we can see that the main source of pollution comes from deliberate dumping or washing of tanks at sea. If we look at the amount of oil released over a year or a decade, this dumping releases 10 to 100 times more oil than oil spills. Although is does not get as much media coverage, the oil released by tank washing arrives on our coastlines in exactly the same way.

Are there ways of finding out which boats are washing out their tanks?

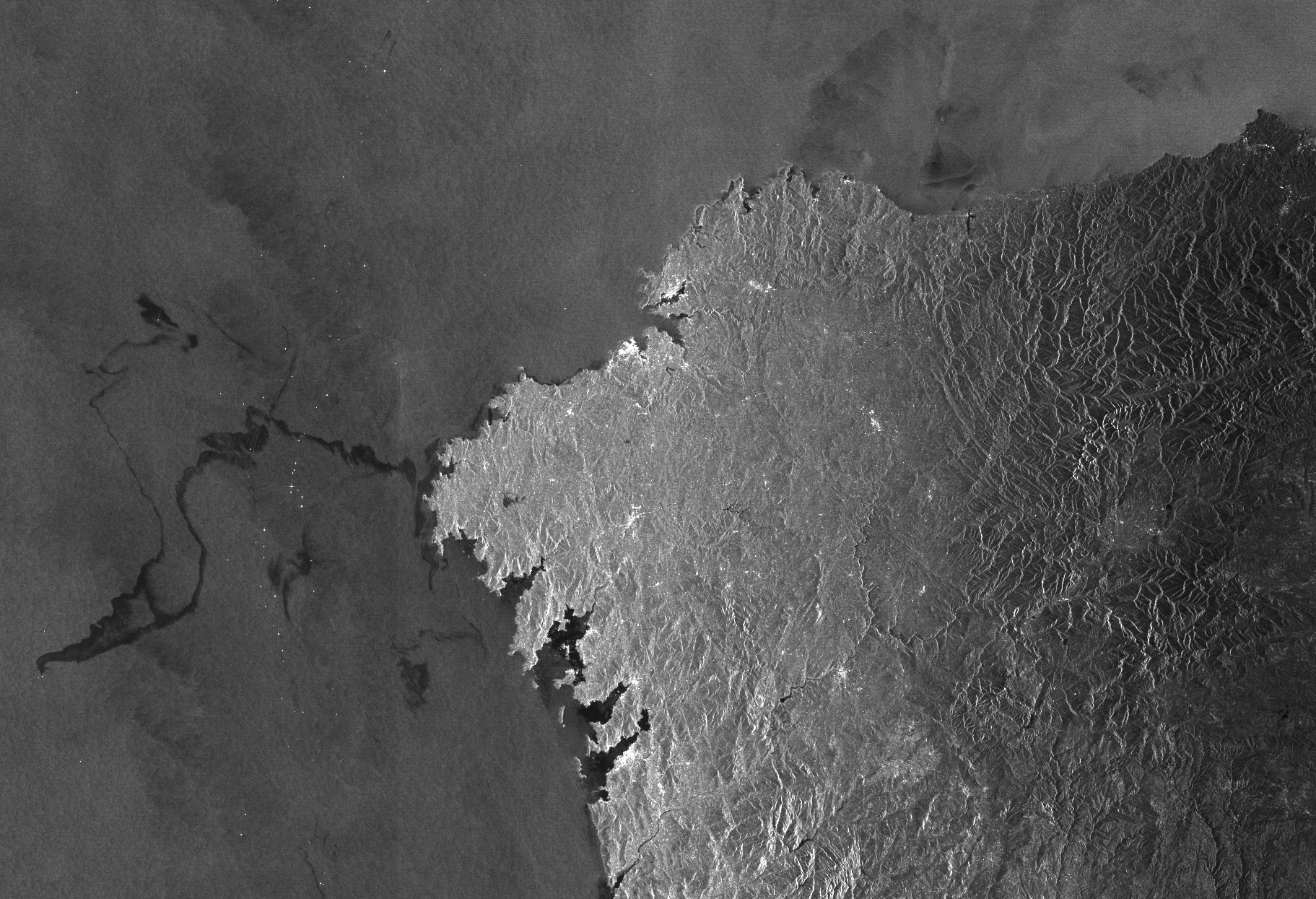

RG: By using sensors placed on satellites, we can have large-scale surveillance technology. The sensors allow us to monitor areas of approximately 100km². The maritime areas close to the coast are our priority, since this is where the tankers stay as they cannot sail on the high seas. Satellite detection methods have improved a lot over the past decade. 15 years ago, detecting tank dumping from space was a fundamental research issue. Today, the technology is used by state authorities to fight against this practice.

How does the satellite detection process work?

RG: The process uses imaging radar technology, which has been available in large quantities for research purposes since the 2000s. This is why IMT Atlantique [at the time called Télécom Bretagne] participated in the first fundamental work on large quantities of data around 20 years ago. The satellites emit a radar wave towards the ocean’s surface, which is reflected back towards the satellite. The reflection of the wave is different depending on the roughness of the water’s surface. The roughness is increased by things such as the wind, currents, or waves and decreased by cold water, algae masses, or oil produced by tank dumping. When the satellite receives the radar wave, it reconstructs an image of the water and displays the roughness of the surface. Natural, accidental or deliberate incidents which reduce the roughness appear as a black mark on the image. The project is a European Research Project which is carried out in partnership with the European Space Agency and a startup based in our laboratories, Boost Technology – which has since been acquired by CLS – and has shown the importance of this technique for detecting oil slicks.

If several things can alter the roughness of the ocean’s surface, how do you differentiate an oil slick from an upwelling of cold water or algae?

RG: It is all about investigation. You can tell whether it is an oil slick from the size and shape of the black mark. Usually, the specialist photo-interpreter behind the screen has no doubt about the source of the mark, as an oil slick has a long, regular shape which is not similar to any natural phenomena. But this is not enough. We have to carry out rigorous tests before raising an alert. We cross-reference our observations with datasets to which we have direct access, such as the weather, temperature and state of the sea, wind, and algae cycles…. All of this has to be done within 30 minutes of the slick being discovered in order to alert the maritime police quickly enough for them to take action. This operational task is carried out by CLS, using the VIGISAT satellite radar data reception station that they operate in Brest, which also involves IMT Atlantique. As well as this, we also work with Ifremer, IRD and Météo France to make the investigation faster and more efficient for the operators.

Detecting an oil spill is one thing, but how easy is it to then find the boat responsible for the pollution?

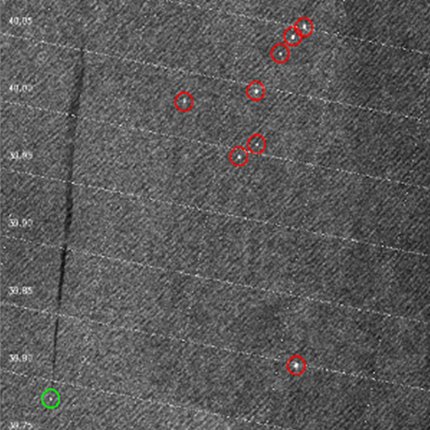

RG: Radar technology and data cross-referencing allow us to identify an oil spill accurately. However, the radar doesn’t give a clear answer as to which boat is responsible for the pollution. The transmission speed of the information sometimes allows the authorities to find the boat which is directly responsible, but sometimes we find the spill several hours after it has been created. To solve this problem, we cross-reference radar data with the Automatic Identification System for vessels, or AIS. Every boat has an AIS which provides GPS information about its location at sea. By identifying where the slick started and the time it was made, we can identify which boats were in the area at the time that could have done a tank dumping.

It is possible to identify a boat suspected of dumping (in green) amongst several vessels in the area (in red) using satellites.

This requires knowing how to date back to when the slick was created and measuring how it changed at sea.

RG: We also work in partnership with oceanographers and geophysicists. How does a slick drift? How does its shape change over time? To answer these questions, we again use data about the currents and the wind. From this data, physicists use fluid mechanics models to predict how the sea would impact an oil slick. We are very good at retracing the evolution of the slick in the hour before it is detected. When we combine this with AIS data, we can eliminate vessels whose position at the time was incompatible with the behavior of the oil on the surface. We are currently trying to do this going further back in time.

Is this research specific to oil spills, or could it be applied to other subjects?

RG: We would like to use everything that we have developed for oil for other types of pollution. At the moment we are interested in sargassum, a type of brown seaweed which is often found on the coast. Its production increases with global warming. The sargassum invades the coastline and releases harmful gases when it decomposes. We want to know whether we can use radar imaging to detect it before it arrives on the beaches. Another issue that we’re working on involves micro-plastics. They cannot be detected by satellites. We are trying to find out whether they modify the characteristics of water in a way that we can identify using secondary phenomena, such as a change in the roughness of the surface. We are also interested in monitoring and predicting the movement of large marine debris…. The possibilities are endless!

Also read on I’MTech

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!