Digital technology, the gap in Europe’s Green Deal

Fabrice Flipo, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]espite the Paris Agreement, greenhouse gas emissions are currently at their highest. Further action must be taken in order to stay under the 1.5°C threshold of global warming. But thanks to the recent European Green Deal aimed at reaching carbon neutrality within 30 years, Europe now seems to be taking on its responsibilities and setting itself high goals to tackle contemporary and future environmental challenges.

The aim is to become a society which is “fair, prosperous and a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy”. This should make the European Union a global leader in the field of the “green economy”, with citizens being placed at the heart of a “sustainable and inclusive growth”.

The deal’s promise

How can such a feat be achieved?

The green deal is set within a long-term political framework for energy efficiency, waste, eco-conception, circular economy, public purchase and consumer education. Thanks to these objectives, the UE aims to reach the long-awaited decoupling:

“A direct consequence of the regulations put in place between 1990 and 2016 is that energy consumption has decreased by almost 2% and greenhouse gas emissions by 22%, while GDP has increased by 54% […]. The percentage of renewable energy has gone from representing 9% of total energy consumption in 2005 to 17% today.”

With the Green Deal the aim is to continue this effort via ever-increasing renewable energies, energy efficiency and green products. The sectors of textiles, building and electronics are now the center of attention as part of a circular economy framework, with a strong focus on repair and reuse, driven by incentives for businesses and consumers.

Within this framework, energy efficiency measures should reduce our energy consumption by half, with the focus on energy labels and the savings they have made possible.

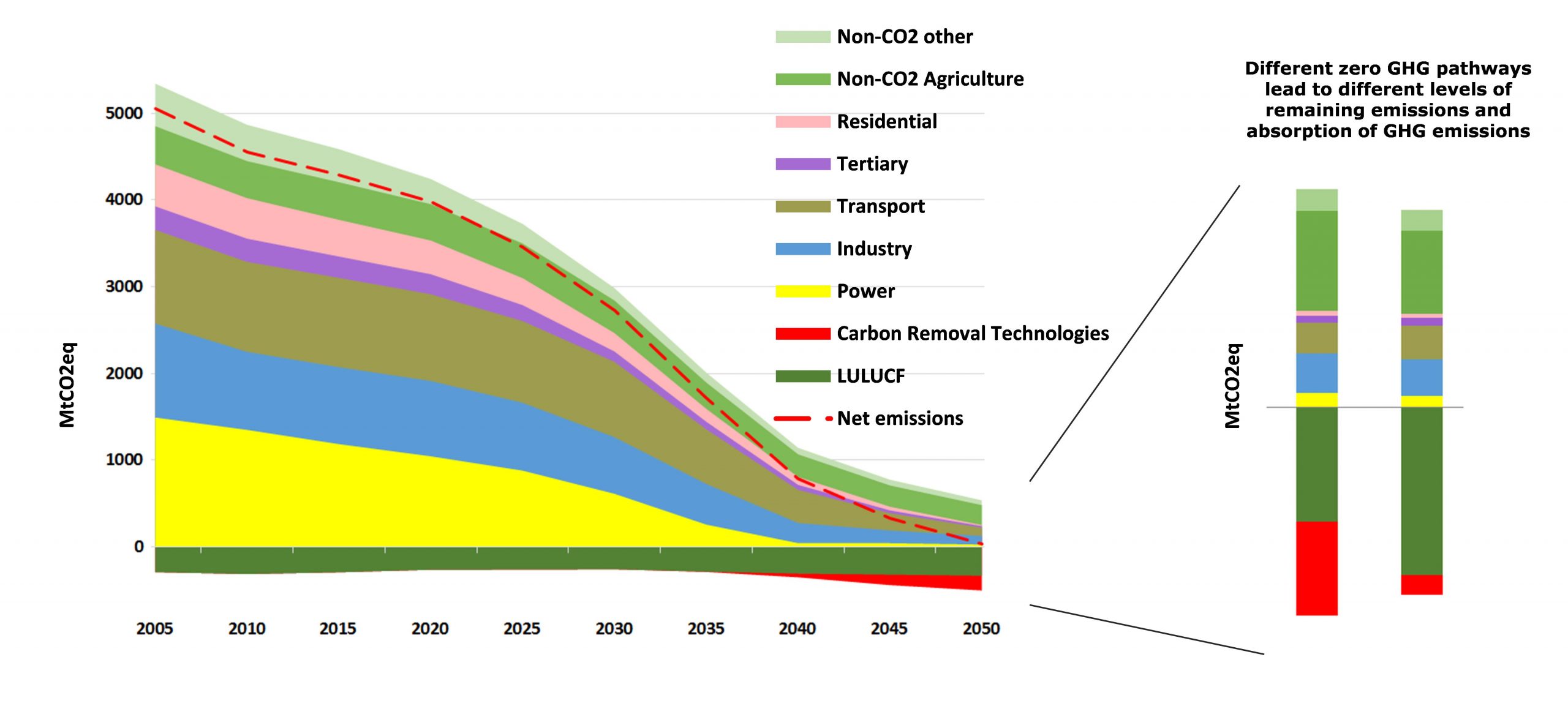

According to the Green Deal, the increased use of renewable energy sources should enable us to bring the share of fossil fuels down to just 20%. The use of electricity will be encouraged as an energy carrier, and 80% of it should be renewable by 2050. Energy consumption should be cut by 28% from its current levels. Hydrogen, carbon storage and varied processes for the chemical conversion of electricity into combustible materials will be used additionally, enabling an increase in the capacity and flexibility of storage.

In this new order, a number of roles have been identified: on one side, the producers of clean products, and on the other, the citizens who will buy them. In addition to this mobilization of producers and of consumers, national budgets, European funding and “green” (private) finance will commit to the cause; the framework of this commitment is expected to be put in place by the end of 2020.

Efficiency, renewable energy, a sharp decrease in energy consumption, promises of new jobs: if we remember that back in the 1970s, EDF was simply planning on building 200 nuclear power plants by the year 2000 – following a mindset which associated consumption and progress – everything now suggests that supporters of the Negawatt scenario (NGOs, ecologists, networks of committed local authorities, businesses and workers) have won a battle which is historic, cultural (in terms of values and realization of what is at stake) and political (backed by official texts).

According to the deal, savings made on fossil fuels could reach between €150 billion and €200 billion per year, to which would be added the amount of health costs that will be avoided, amounting to €200 billion a year and the prospect of exporting “green” products.. Finally, millions of jobs may be created, with retraining mechanisms for the sectors that are the most impacted, and support for low-income households.

Putting the deal to the test

A final victory? On paper, everything points that way.

However, it is not as simple at it seems, and the UE itself recognizes that improvements in the field of energy efficiency and the decrease in glasshouse gas emissions are currently stalling..

This is due to the following factors, in order of importance: economic growth; the decrease in energy efficiency savings, especially in the airline industry; the sharp increase in the number of SUVs; and finally, the upward adjustment of real vehicle emissions, following the “diesel gate” scandal (+30 %).

More seriously, the EU’s net emissions, which include those generated by imports and exports, have risen by 8% during the 1990-2010 period.

Efficiency therefore has its limits and savings are more likely to be made at the start than at the end.

The digital technology challenge

According to the Green Deal, ‘Digital technologies are a critical enabler for attaining the sustainability goals of the Green deal in many different sectors”: 5G, CCTV, Internet of things, cloud computing or AI. We have our doubts, however, as to whether that is true.

Several studies, including by the Shift Project, show that emissions from the digital sector have doubled between 2010 and 2020. They are now higher than those produced by the much-criticized civil aviation sector. The digital applications put forward by the European Green Deal are some of the most energy consuming, according to several case scenarios.

Can the increase in usage be offset by energy efficiency? The sector has seen tremendous progress, on a scale not seen in any other field. The first computer, the ENIAC, weighed 30 tons, consumed 150,000 watts and could not do more than 5,000 operations per second. A modern PC consumes 200 to 300 W, for the same available power as a supercomputer of the early 2000s which consumed 1.5 MW! Progress knows no bounds…

However, the absolute limit (the “Landauer limit”) was identified in 1961 and confirmed in 2012. According to the semiconductor industry itself, the limit is fast approaching in terms of the timeframe for the Green Deal, at a time when traffic and calculation power are increasing exponentially. Is it therefore reasonable to continue becoming increasingly dependent on digital technologies, in the hope that efficiency curves might reveal energy consumption “laws”?

Especially when we consider that the gains obtained in terms of energy efficiency have little to do with any shift towards more ecology-oriented lifestyles: the motivations have been cost, heat removal and the need to make sure our digital devices could be mobile so as to keep our attention at all times.

These limitations on efficiency explain the increased interest in more sparing use of digital technologies. The Conseil National du Numérique presented its roadmap shortly after Germany. However, the Green Deal is stubbornly following the same path: a path which consists in relying on an imaginary digital sector which has little in common with the realities of the sector.

Digital technologies, facilitating growth

Drawing from a recent article, the Shift Project sends a warning: “Up until now, rebound effects have tuned out to exceed the gains brought by technological innovation.” This conclusion has once more been recently confirmed.

For example, the environmental benefits of distance working have in fact been much smaller than those we were expecting intuitively, especially when not combined with other changes in the social ecosystem. Another example is that in its 2019 “current” scenario, the OECD predicted a threefold increase in passenger transport between 2015 and 2050, facilitated (and not impeded) by autonomous vehicles.

Digital technologies are a growth factor first and foremost, as Pascal Lamy, then Head of the WTO, said when he stated that globalization is based on two innovations: Internet and the container. An increase in digital technologies will lead to more emissions. And if this is not the case, it will be because of a change in how we approach ecology, including digital technologies.

We are justified in asking the question of what it is the Green Deal is really trying to protect: the climate or the digital markets for big corporations?

[divider style=”dotted” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Fabrice Flipo, Professor of social and political philosophy, epistemology and history of science and technology at Institut Mines-Télécom Business School

This article is republished from The Conversation under the Creative Commons license. Read the original article (in French) here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!