The world’s oldest building material is also the most environmentally friendly

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.

By Abdelhak Maachi and Rodolphe Sonnier, IMT Mines Alès.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]espite the recommendations of IPCC experts, who in 2018 recommended that greenhouse gas emissions be reduced by 40 to 70% by 2050 in an attempt to limit the impacts of the climate crisis, global CO2 output increased by 0.6% in 2019.

Among the efforts made towards reducing the CO2 emitted through human activity, earth, the world’s most widespread raw material, has an essential role to play. Let’s not forget that the building sector alone generates nearly 40% of annual greenhouse gas emissions.

An ancient and global history

11,000 years ago, Homo sapiens was already building with earth in the region of present-day Syria. This age-old eco-material is still one of the world’s main building materials today. It is estimated to represent more than a third in the countries of the South.

Examples of earthen architecture, from the most modest to the most monumental, can be found on all continents and in all climates. 175 sites, wholly or partially built using this material, are classified by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites, highlighting the durability of this construction method.

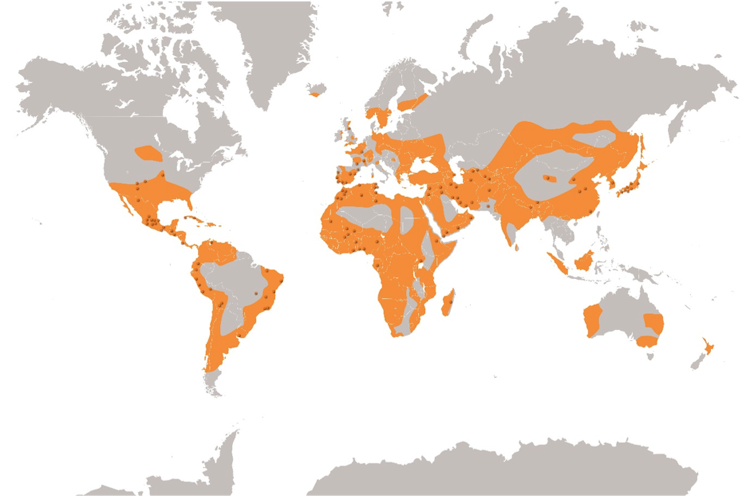

In orange, the regions where earth is used in construction. The dots indicate the main architectural sites on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Source: Craterre.

Examples include the Grand Mosque of Djenné in Mali, built in 1907. It remains one of the largest mud brick buildings in the world and is one of the emblems of the country’s culture. In China, the Great Wall has sections several kilometers long built from earth where stone was not available locally. Also worthy of note is the 16th-century town of Shibam in Yemen, the world’s first dense, vertical town with high-rise buildings about 30 meters high, built entirely of molded mud bricks (called “adobes”). Due to the ongoing civil war in the country, the city is now on the UNESCO World Heritage in Danger list.

In Morocco, the four imperial cities – Fez, Marrakesh, Meknes and Rabat – are also classified as World Heritage Sites because of their traditional medinas built of adobe and rammed earth (pisé). The country also features prodigious fortresses made from ochre earth, called ksars and kasbahs. The Ksar of Ait-Ben-Haddou is an emblematic example of the traditional Amazigh architecture of southern Morocco.

Shibam (Yemen) and its brick towers. Source: Kebnekaise/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

In Marrakesh (Morocco). Source: Luca Di Ciaccio/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

In Europe, earthen constructions are not restricted to rural environments. In Granada, the dazzling Alhambra palace (meaning “red” in Arabic, in reference to the color of the earth), was largely built from rammed earth in the 13th century, in particular its ramparts.

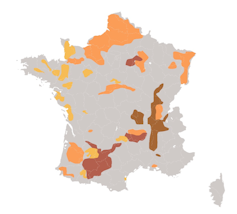

France is one of the few countries featuring earthen heritage buildings using the 4 main traditional techniques – rammed earth (pisé), adobe, torchis cob and bauge cob – and where the majority of the earthen buildings often date back more than a century. Lyon is home to some remarkable examples of earthen architecture. In the Croix-Rousse neighborhood, people have been living in 4 and 5-floor rammed earth buildings since the 1800s.

The defense towers of Alhambra in Granada (Spain). Source: Moli Sta Elena/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Building with what is under our feet

The earth is made up of minerals, organic matter, water and air. These minerals, composed mainly of silicates – quartz, clays, feldspars and micas – and carbonates, are the result of physical and chemical alteration of a source rock. The earth used for building (the raw material), which is essentially mineral, is easily removed from the ground, underneath the layer of soil that is rich in organic matter (humus) and is used for plant production.

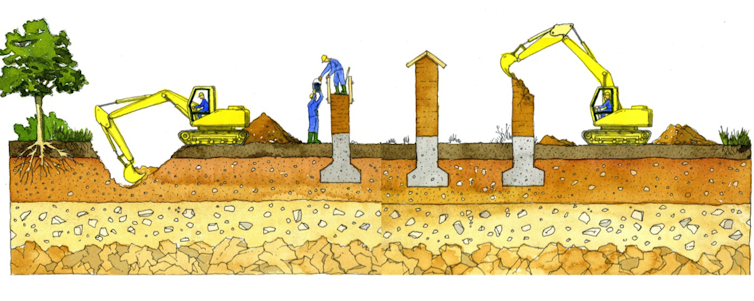

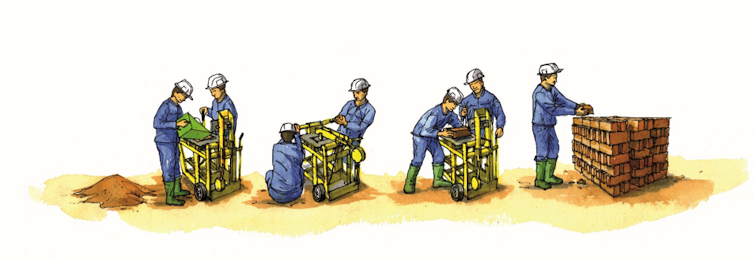

After extraction using rudimentary or more elaborate tools, the earth (consisting of clay, silt, sand and possibly gravel and pebbles) is transformed into building material using traditional or more contemporary methods. The methods can be grouped into four main categories.

- Compacted earth, not saturated with water: to make rammed earth walls (pisé) and blocks of compressed earth.

- Stacked or molded earth: to make bauge cob walls and adobes.

- Earth mixed when wet with plant fibers: to make torchis cob (to fill a wooden framework), straw earth, hemp earth, etc.

- Earth poured in a liquid state into framework, such as fluid or self-consolidating concrete.

Life cycle of earthen building materials: extraction, construction, use, demolition and recycling. Source: Arnaud Misse.

Rammed earth (pisé): earth containing little moisture is compacted with the help of a tamper into wooden formwork. Source: Arnaud Misse.

Blocks of compressed earth: earth containing little moisture is compressed in molds using a press. Source: Arnaud Misse.

Easy to work with, healthy and environmentally friendly

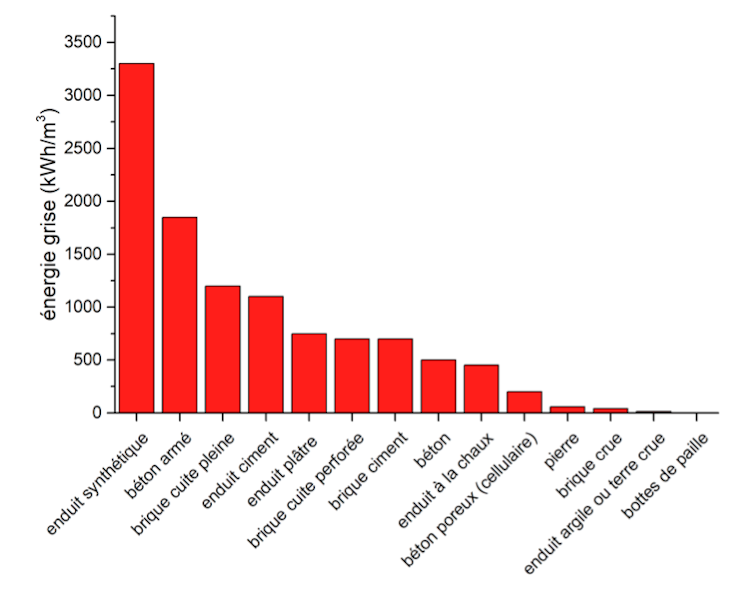

There are a lot of advantages to using earth: it is a natural material, abundantly and locally available (transport is often nil), with low embodied energy (energy consumed throughout the life cycle of a material) and infinitely recyclable. It is raw and diversified, and offers a variety of granularities, natural colors and lively textures, for a minimalist aesthetic.

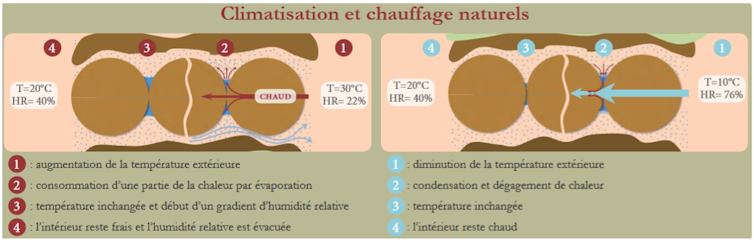

Earth also provides hygrothermic natural comfort, optimal acoustics and a healthy indoor atmosphere. It provides hygrometric regulation and solid walls provide good thermal inertia and sound insulation. It emits no VOCs (volatile organic compounds) and absorbs odors. These virtues have been empirically understood for thousands of years, but have now been confirmed scientifically.

Unlike industrialized and globalized materials, earth is easy to work with and poses no health risk. It thus helps to promote participatory building sites and self-built constructions (especially for the most disadvantaged), to value the diversity of construction cultures and to stimulate local development.

Earthen construction also contributes to the recovery of excavated land in large cities considered as waste. While the Greater Paris Express construction site will generate 40 million tons of earth by 2030, the “cycle terre” project aims to transform part of this “waste” into eco-materials for construction in a circular economy.

These eco-responsible advantages make earth a building material of the future, an alternative to energy-intensive and polluting building materials such as fired brick or cement (nearly 7% of global CO2 emissions), and a solution to be promoted in the building industry to respond to the global housing crisis (affecting one billion people) and the climate emergency, as hoped by the signatories of the “Manifesto for a Happy Frugality”.

Limitations to be overcome

But earth also has its limits. The main problem is its sensitivity to water. To overcome this, mud walls are traditionally protected, especially in rainy climates, with a base (made of stone for example) to prevent moisture soaking up through capillary action, and a roof overhang to protect against erosion due to rain.

A small amount of cement is sometimes added to limit sensitivity to water and to increase, albeit modestly, mechanical properties. However, this “stabilization” technique is open to criticism because it impacts the ecological advantages and penalizes the life cycle of the material.

Distribution of architectural heritage made from earth. In orange: torchis cob, in brown: rammed earth (pisé), in yellow: bauge cob and in red: adobe. Source: Craterre.

Earth represents 15% of French buildings. However, the percentage of new buildings made of earth remains close to zero at the national level, although it is on the increase. The omnipresent reign of concrete, the hyper-industrialized context of construction, lobbying, inappropriate regulations, unfavorable prejudices (it is often seen as a primitive material for poor countries!), the lack of knowledge among decision-makers, engineers and project owners, are all reasons that explain the marginalization and ostracism from which this material suffers.

To overcome these barriers, earthen construction requires appropriate specific regulations for its implementation and maintenance, as well as adapted tests taking into account its specificities and complexity; evaluating its physical properties and durability. The development of earthen construction also requires scientific research, education, appropriate training of future designers and builders and promotion.

But earth, along with other ecomaterials such as wood, stone and bio-based insulators (such as hemp and straw), should undoubtedly contribute to building the resilient and autonomous city of tomorrow.

Construction of Terra Janna in Marrakesh (Morocco): an earthen construction training center (Centre de la Terre) and a guest house built entirely using the adobe technique. This is an example of contemporary environmentally responsible earthen architecture. Source: Denis Coquard.

[divider style=”dotted” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Arnaud Misse (CRAterre), Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Grenoble), Laurent Aprin, Marie Salgues, Stéphane Corn, Éric Garcia-Diaz (IMT Mines Alès) and Philippe Devillers (Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Montpellier) are co-authors of this article.

Abdelhak Maachi doctoral student in material science, Mines Alès – Institut Mines-Telecom and Rodolphe Sonnier, assistant professor at the Ecoles des Mines, Mines Alès – Institut Mines-Telecom

This article was republished from The Conversation under the Creative Commons license. Read the original article here (in French).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!