Putting sound and images into words

Can videos be turned into text? MeMAD, an H2020 European project launched in January 2018 and set to last three years, aims to do precisely that. While such an initiative may seem out of step with today’s world, given the increasingly important role video content plays in our lives, in reality, it addresses a pressing issue of our time. MeMAD strives to develop technology that would make it possible to fully describe all aspects of a video, from how people move, to background music, dialogues or how objects move in the background etc. The goal: create a multitude of metadata for a video file so that it is easier to search for in databases. Benoît Huet, an artificial intelligence technologies researcher at EURECOM — one of the project partners — talks to us in greater detail about MeMAD’s objectives and the scientific challenges facing the project.

Can videos be turned into text? MeMAD, an H2020 European project launched in January 2018 and set to last three years, aims to do precisely that. While such an initiative may seem out of step with today’s world, given the increasingly important role video content plays in our lives, in reality, it addresses a pressing issue of our time. MeMAD strives to develop technology that would make it possible to fully describe all aspects of a video, from how people move, to background music, dialogues or how objects move in the background etc. The goal: create a multitude of metadata for a video file so that it is easier to search for in databases. Benoît Huet, an artificial intelligence technologies researcher at EURECOM — one of the project partners — talks to us in greater detail about MeMAD’s objectives and the scientific challenges facing the project.

Software that automatically describes or subtitles videos already exists. Why devote a Europe-wide project such as MeMAD to this topic?

Benoît Huet: It’s true that existing applications already address some aspects of what we are trying to do. But they are limited in terms of usefulness and effectiveness. When it comes to creating a written transcript of the dialogue in videos, for example, automatic software can make mistakes. If you want correct subtitles you have to rely on human labor which has a high cost. A lot of audiovisual documents aren’t subtitled because it’s too expensive to have them made. Our aim with MeMAD is, first of all, to go beyond the current state of the art for automatically transcribing dialogue and, furthermore, to create comprehensive technology that can also automatically describe scenes, atmospheres, sounds, and name actors, different types of shots etc. Our goal is to describe all audiovisual content in a precise way.

And why is such a high degree of accuracy important?

BH: First of all, in its current form audiovisual content is difficult to access for certain communities, such as the blind or visually impaired and individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing. By providing a written description of a scene’s atmosphere and different sounds, we could enhance the experience for individuals with hearing problems as they watch a film or documentary. For the visually impaired, the written descriptions could be read aloud. There is also tremendous potential for applications for creators of multimedia content or journalists, since fully describing videos and podcasts in writing would make it easier to search for them in document archives. Descriptions may also be of interest for anyone who wants to know a little bit about a film before watching it.”

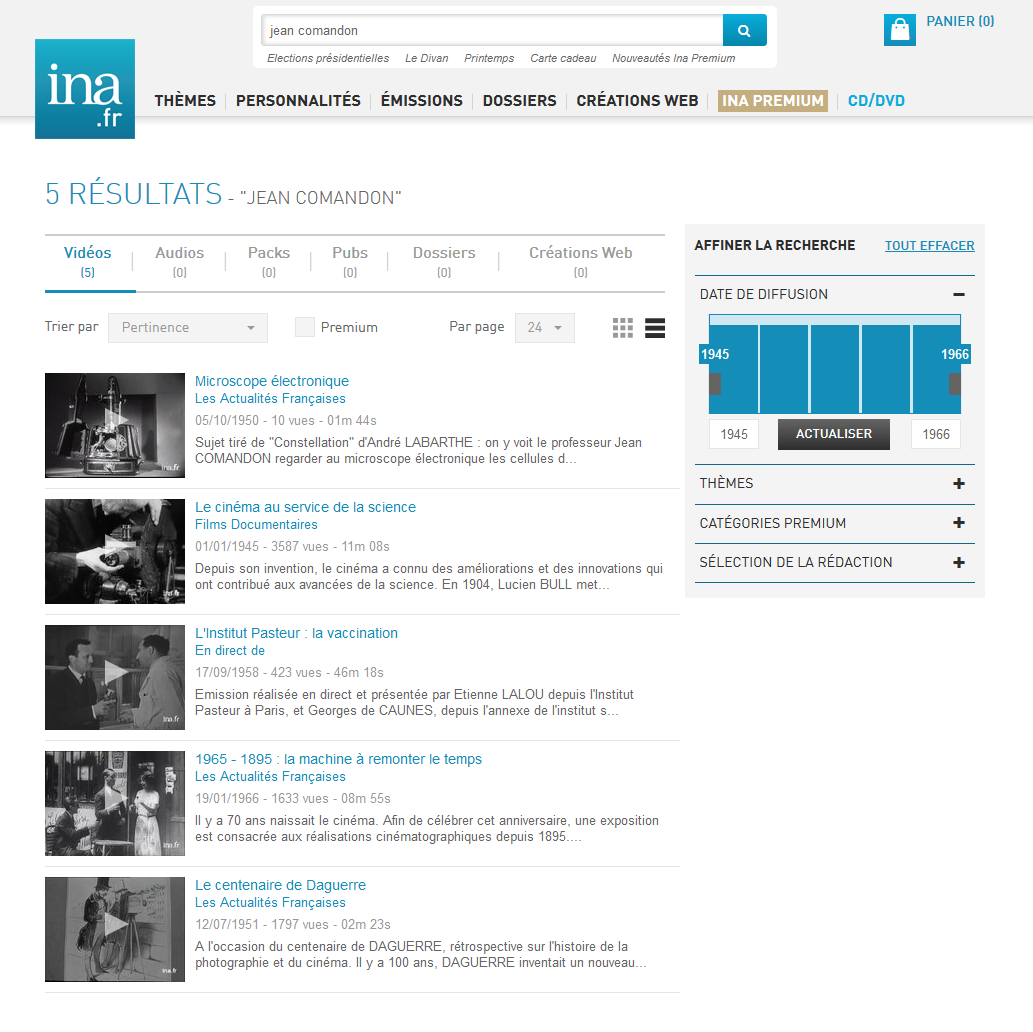

The National Audiovisual Institute (INA), one of the partner’s projects, possesses extensive documentary and film archives. Can you explain exactly how you are working with this data?

BH: At EURECOM we have two teams involved in the MeMAD project who are working on these documents. The first team focuses on extracting information. It uses technology based on deep neural networks to recognize emotions, analyze how objects and people move, the soundtrack etc. In short, everything that creates the overall atmosphere. The scientific work focuses especially on developing deep neural network architectures to extract the relevant metadata from the information contained in the scene. The INA also provides us with concrete situations and the experience of their archivists to help us understand which metadata is of value in order to search within the documents. And at the same time, the second team focuses on knowledge engineering. This means that they are working on creating well-structured descriptions, indexes and everything required to make it easier for the final user to retrieve the information.

What makes the project challenging from a scientific perspective?

BH: What’s difficult is proposing something comprehensive and generic at the same time. Today our approaches are complete in terms of quality and relevance of descriptions. But we always use a certain type of data. For example, we know how to train the technology to recognize all existing car models, regardless of the angle of the image, lighting used in the scene etc. But, if a new car model comes out tomorrow, we won’t be able to recognize it, even if it is right in front of us. The same problem exists for political figures or celebrities. Our aim is to create technology that works not only based on documentaries and films of the past, but that will also able to understand and recognize prominent figures in documentaries of the future. This ability to progressively increase knowledge represents a major challenge.

What research have you drawn on to help meet this scientific challenge?

BH: We have over 20 years of experience in research on audiovisual content to draw on. This justifies our participation in the MeMAD project. For example, we have already worked on creating automatic summaries of videos. I recently worked with IBM Watson to automatically create a trailer for a Hollywood film. I am also involved in the NexGenTV project along with Raphaël Troncy, another contributor to the MeMAD project. With NexGenTV, we’ve demonstrated how to automatically recognize the individuals on screen at a given moment. All of this has provided us with potential answers and approaches to meet the objectives of MeMAD.

Also read on I’MTech

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!