Fraud on the line

An unsolicited call is not necessarily from an unwelcome salesman. It is sometimes a case of a fraud attempt. The telephone network is home to many attacks and most are aimed at making a profit. These little-known types of fraud are difficult to recognize and difficult to fight.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

This article is part of our series on Cybersecurity: new times, new challenges.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

How many unwanted phone calls have you received this month? Probably more than you’d like. Some of these calls are undoubtedly from companies you have signed a contract with. This is the case with your telephone operator which regularly assesses its customer satisfaction. Other calls are from telemarketing companies that acquire phone numbers through legal trade agreements. Energy suppliers in particular buy lists of contacts in their search for new customers. On the other hand, some calls are completely fraudulent. Ping calls, for example, are made by calling a number for a few seconds to leave a missed call on the recipient’s telephone. The recipient who returns the call is then forwarded to a premium-rate number. The call is often redirected to a foreign location, an expensive destination. The service the caller connects with then offers them to sign up for a contract in exchange for a subsequent payment. The International Telecommunications Union sees these “cash-back” schemes as abusive. “Some calls are also made by robots which scan lists of numbers to identify if they belong to individuals or companies,” Aurélien Francillon explains. As an expert in network security, this researcher at EURECOM works specifically on the issue of telephone fraud.

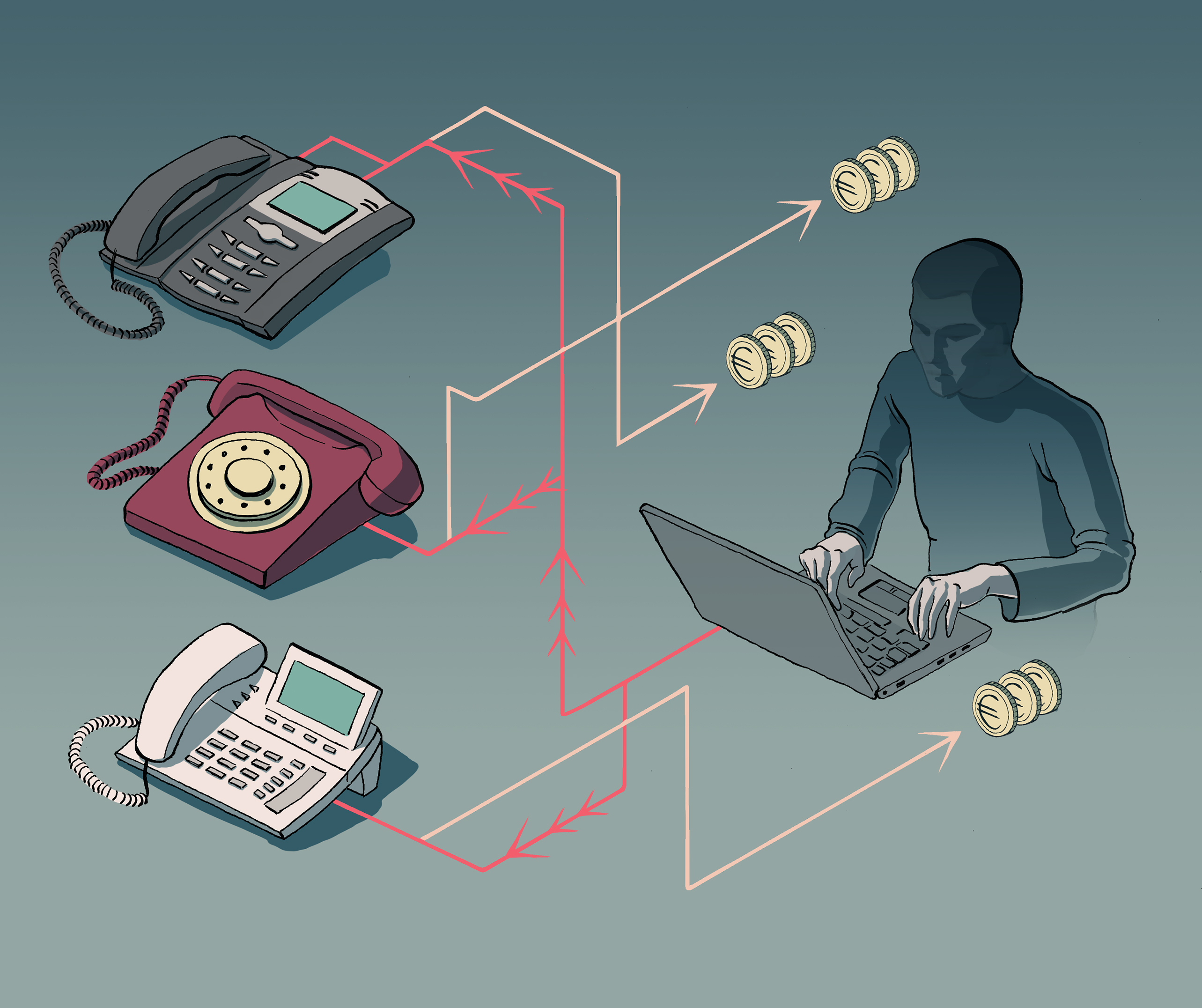

Although the scientific community is tackling this issue head on, the topic is more extensive than it first appears. Individuals are not the only victims; companies are also vulnerable to these types of attacks. In order to direct external calls and manage calls between internal telephone lines, companies must establish complex telephone systems. “Companies have telephone exchanges which ensure all the private telephones are interconnected,” explains Aurélien Francillon. These exchanges are called PABX units (private automatic branch exchange) and they typically enable functions such as “do not disturb” and “call forwarding”. However, attackers can take control of these exchanges. “Scammers often carry out a PABX attack over the weekend when the employees are not present,” the researcher explains. “Again, they will call international, premium-rate numbers using the controlled lines to make money.” The attack is only detected a few days later. In the meantime, the cybercriminals have potentially made thousands of euros.

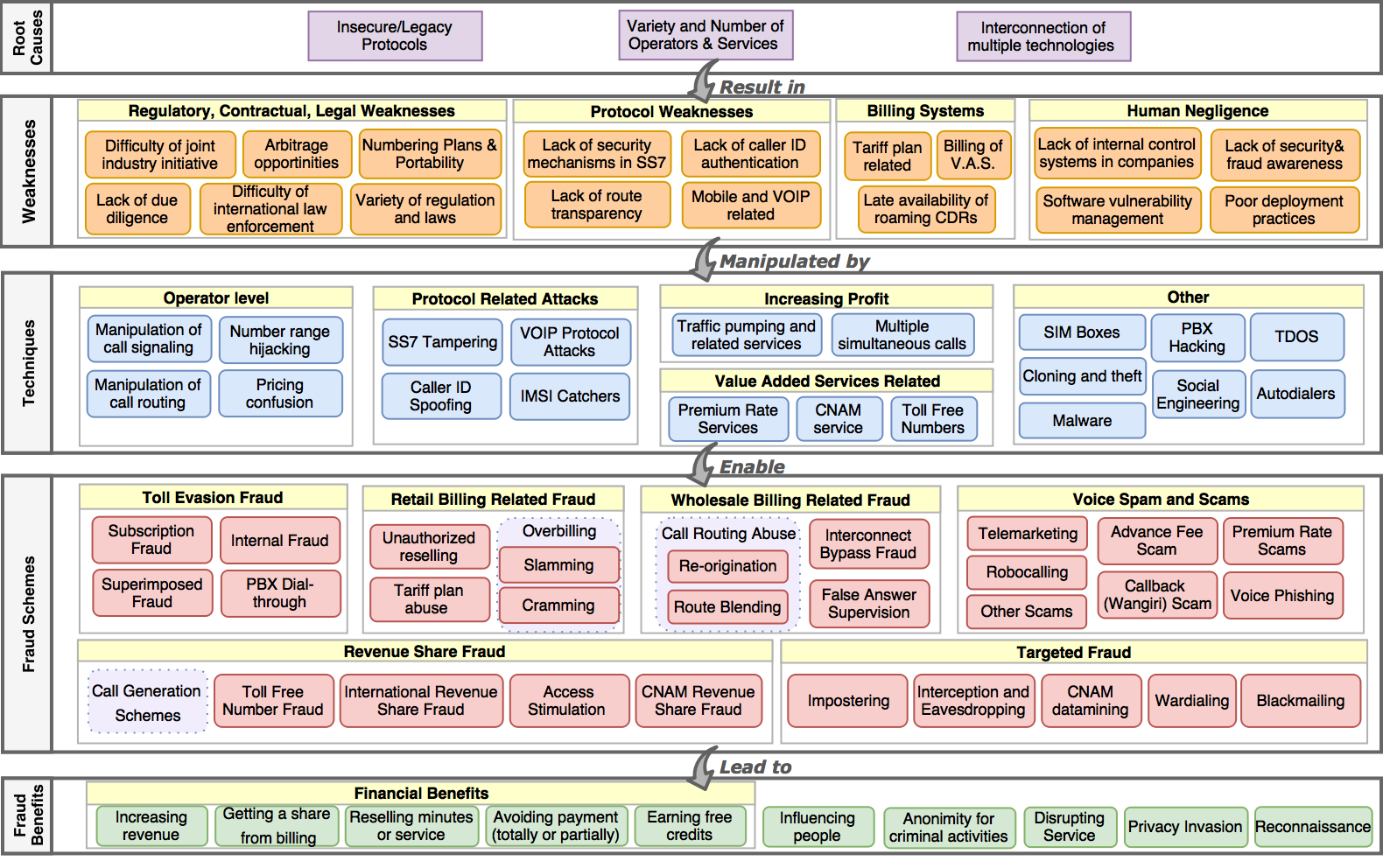

Taxonomy of fraud

The first challenge in the fight against such attacks is understanding the motivations and procedures. The same technique, such as PABX hacking, is not necessarily used by all scammers for the same purposes. And several means can be used for the same objective, such as extortion. To make sense of the issue, the researchers at EURECOM developed a taxonomy of fraud. “It is a grid which brings together all the knowledge on the attacks to better classify them and understand the patterns scammers use,” Aurélien Francillon explains. This is a big contribution to the scientific community. Until now there had not been a global and comprehensive vision of the topic of telephone network security. To create this taxonomy, the researcher and a PhD student, Merve Sahin, first needed to define fraud. They believe it is a “means of obtaining illegitimate profit by using a specific technique made possible by a weakness in a system, which is itself due to root causes.” It was in listing these deeper, root causes behind the flaws as well as the resulting weaknesses and techniques they enabled that the researchers succeeded in creating a complete taxonomy in the form of a grid.

Nearly 150 years of technological developments make studying flaws in the telephone network a complex matter.

Thanks to a better understanding of the threats, the scientists can now consider defense strategies. This is the case for “over-the-top” or OTT bypass fraud, which involves diverting a call to make a profit. When a user wants to call someone in a foreign country, the operator delegates the routing of the call to transit operators. These operators transport the call over continents or oceans using their cables. To optimize rates, these operators can themselves delegate the call routing to local operators who can transfer the calls for a country, for example. “Each operator involved in the routing will recover part of the income from the call. Each party’s goal is to sell their routing service to the operators for which they will route the calls at a higher price than they will pay the next operators which will take care of terminating the calls.” For one call, over a dozen stakeholders can be involved, without the caller’s operator necessarily knowing it. “This leads to gray areas that leave room for little-known stakeholders whose legitimacy and honesty cannot necessarily be ensured. Among them are inexpensive, malicious operators who, at the end of the chain, will redirect the call to a vocal chat application on the recipient’s mobile phone. The operator of the person receiving the call therefore does not receive any income on this call, which is why it is called “over-the-top” (OTT), since it passes over the stakeholders who are supposed to be involved.

Because so many stakeholders are involved in this type of fraud, the taxonomy helps to identify the relationships between them. “We had to understand the international routing system, and the billing process between the operators, which works somewhat like a stock market,” Aurélien Francillon explains. After studying the stakeholders and mechanisms, the researchers were able to reflect on how cases of fraudulent routing could be detected… And they realized that there is currently no technical solution to prevent them. It is virtually impossible to determine if a voice stream on IP that arrives at a mobile application — sometimes encrypted and in proprietary formats — is from a classic telephone call (and there has been a bypass) or from a free call made using an application (in which case there is no bypass). OTT bypass fraud is therefore hard to detect. However, this does not mean that no solutions exists, rather it is necessary to look to other solutions that are not technical ones. “The most relevant solutions on this type of subject are more economic or legal,” the researcher admits. “However, we believe it is crucial to study these phenomena in a scientific manner in order to make the right decisions, even if they are not purely technical.”

Using legal means if necessary

Adapting legislation to prevent these abuses is another approach that has already been used in other cases. To prevent too many spam phone calls, French law provided for the establishment of a list for opposing cold sales calls. Since 1 June 2016, all consumers have the right to sign up to be added to the Bloctel list. The service ensures that the lists telemarketers provide are cleaned before the next telemarketing campaign. To estimate the impact of such a measure, Aurélien Francillon and his team have done some preliminary work at a European level. They signed 800 numbers up for the block lists of 8 countries in Europe. The objective was to comparatively assess the effectiveness of the lists between countries. Sometimes, the lists truly reduce the number of unwanted calls received, and this is the case for France in particular. However, they sometimes have the opposite effect. In England, the block lists are sent to the telemarketing companies so that they themselves remove the numbers of individuals who have expressed their opposition to telemarketing. “Obviously, some companies are not playing along,” Aurélien Francillon observes. “We even observed a case in which only the numbers on the block list had been called, suggesting that it had been used to target people.”

This is one of the limitations of the legal approach: just like the technical solution, it depends on how it is implemented. If it is well done, it can prove to be a good alternative when technology does not offer a solution to such complex problems. In the Bloctel example, the solution also relies heavily on information from consumers. “It is important to give them a comprehensive vision of the problem so that they can understand what can be hidden behind a sales call or a missed call on their mobile,” the researcher insists. Thanks to the taxonomy that EURECOM has developed, we expect that the scientific community will be able to better describe and study all cases of potential fraud. Before looking for solutions, this will first help effectively inform individuals and companies about the risks on the line.

[box type=”shadow” align=”” class=”” width=””]

A robot fighting spam calls?

To help combat unwanted calls, developers have designed Lenny, a conversational robot intended to make telemarketers waste as much time as possible. With the voice of an elderly person, he regularly asks to have questions repeated, or begins telling a story about his daughter that is completely unrelated to the telemarketer’s question. Unlike the Alexia and Google Home assistants, Lenny’s interactions are simply prerecorded and are looped in the conversation.

Researchers at EURECOM and Télécom ParisTech have studied what makes this robot work so well — it has made some sellers waste 40 minutes of their time! Based on 200 conversations recorded with Lenny, they classified different types of calls: requests for funding for political parties, spam, aggressive or polite sellers, etc. The feature that makes Lenny so effective is that he appears to have been designed based on the results of conversational analysis, with initial results dating back to the 1970s. It identifies the silences in conversations which triggers prerecorded sequences. His responses are particularly credible because they include changes in intonation and turning points in the conversation.

[/box]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!